I’m not usually one to make grand new year’s resolutions. The past few years, my resolutions took the form of “read a difficult book this year”. Difficult being defined as (a) lengthy and (b) not my usual fare. With this “system” I’ve managed to read:

- (2016) Gödel, Escher, and Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid by Douglas Hofstadter. I’ve wanted to read this since I heard about it in college. It’s an extremely unusual book with lots of eureka moments for me. Maybe Hofstadter’s enthusiasm is really just infectious. This is a book whose pronouncements on artificial intelligence was just way off but I would nonetheless still recommend for introductory insight and intuitive explainers for some pretty abstract math. And more! As Hofstadter will tell you, this isn’t a Math or a Computer Science book. He has a very specific topic in mind—which I think is a fair assessment of his own work—but this book is really just unusual in that it touches on a lot of things.

- (2017) A Brief History of Time and The Universe in a Nutshell by Stephen Hawking. Fun fact: my copy is a volume combining the two books inside a single cover, in glossy color print. I got this from the Manila International Book Fair back in 2012 (yep the same book fair that triggered this post). Sat on my shelf for five years before I worked through it. Shows you the extent of my tsundoku.

- (2018-2019) A History of the World in Twelve Maps by Jerry Brotton. I’ve always been fascinated with maps and always been fascinated with looking at history through unusual, maybe even mundane, objects. This book just called out to me. As you see around this time, I’ve failed to keep up with my goal of finishing a difficult book within the calendar year. Not sure what happened, but I could guess. I even brought this book with me to Germany.

- (2019-2020) The Hero With a Thousand Faces by Joseph Campbell. My introduction to The Campbellian Hero’s Journey was from internet discussions about Po the Kung Fu Panda. This book is a dense treatise, and though frequently cited in literary analysis, I’ve found it to be more anthropological than literary. To be honest, I’m not too convinced with Campbell’s thesis here—as a matter of style he’s not as scientific as I’d want him to be; for example, he doesn’t try to address how his theory can be falsified. But I still recommend this not just because it will give you context in a lot of contemporary discussions about literature (including films, TV shows, etc., not just written stories), but also because I think Campbell is actually on to something, despite the lack of rigor on his methodology, and he offers an interesting insight into the human psyche. I finished this book this year while in social distancing mode.

So, I don’t really have a book this year that would qualify, unless maybe I start tackling German texts. And actually, I have! I’ve been reading Das Labyrinth des Fauns, Cornelia Funke’s adaptation of the acclaimed Guillermo del Toro movie. This story is just great, I don’t even notice it’s not in English, in either medium (recall: the del Toro movie was a Spanish production).

Oh, I’ve also made a few more traditional resolutions.

- 2019, definitely influenced by my plans to leave for Germany, I started journaling. I even wished for a fancy journal notebook from our office exchange gift.

- 2020, I resolved to be more focused. To be very honest, I didn’t do that well on this resolution. If it’s any consolation, the Wacom tablet kinda helped me make up for it, scored goals in the dying minutes, if you will. The past few days (if not the last few weeks of 2020, when I already had my Wacom) I’ve absolutely nerd sniped myself into digital painting. I’ve figured out that my learning style relies heavily on experimentation. That’s why I’ve so far had a hard time, experimenting with the art lessons I’ve been learning from Youtube (like, color theory, anatomy-grounded figures). Erasing is easy, yes, but not always clean, which sucks if you’re trying to get a lot of things right. Digital painting is still a lot of effort but it’s more convenient. I feel like I’m back in school. I’ve been doing a lot of things that apply the things I learn but I’m not really producing anything remotely portfolio-worthy—exactly how I felt during my Computer Science undergrad.

So what’s it for this year? I should definitely continue to be more focused but that also means I should really stick to a strict sleep cycle regimen, something I find hard to do during the gloriously long days of summer (there’s a lot more to this statement but it’s probably a blog post of its own).

Maybe be more creative, be more fearless in my creative endeavors. If you need to churn out a thousand crappy things to create one good thing, then let’s churn through one thousand crappy things with an indomitable spirit. In fact, I have an art project I’ve been working on lately, also what prompted me that I might need a Wacom tablet for this one. Maybe you can argue this project is a coping strategy for all the 2020 distancing, but also, it’s not surprising if you know me as well as I do. So whatever. I don’t care what people say, let’s just do it!

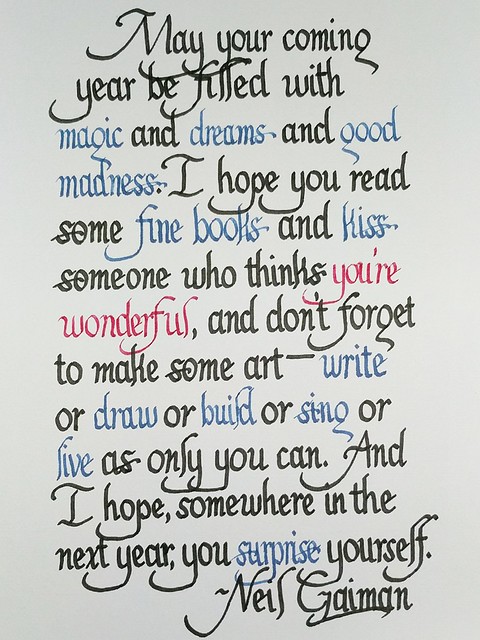

And oh, it’s new year. This Neil Gaiman quote definitely fits. Calligraphed by yours truly, circa 12/29/2018, Speedball with Higgins ink on Canson watercolor paper.