It was bittersweet finishing The Sandman.

Well, endings of all kinds tend to be bitter, regardless of whether it is happy, or sad, or cathartic. But even more so when what ended was something which made you smile, gave you good dreams, and was a welcome distraction from all the things you should actually be focusing on. Such was The Sandman to me. It did not help my poor emotions that it ended with The Wake–a volume so gorgeous it induces synesthesia. I dare you to read The Wake and not hear Morpheus’ funeral dirge playing as words are said about the deceased, or the song sung by the panels masterfully dictating the tempo of the story.

The final volume has transcended its designation as “graphic novel” into the realm of deep, epic elegy. A fitting one for the King of Dreams, consist of not just words but pictures. And boy don’t each picture tell a thousand stories?

I have a long history with The Sandman. My first encounter with it was as a grade school student, seeing it mentioned in a local otaku magazine due to Yoshitaka Amano’s (of Final Fantasy fame) eventual involvement in the form of The Dream Hunters. In a long chain of association, of one-thing-lead-to-another’s, I ended up finding myself spending late nights Wikipedia hopping, trying to piece out the story, to no avail. And with good reason. In The Sandman, Neil Gaiman makes full use of his medium; mere synopses could do no justice. That the term “graphic novel”, so attached to Sandman thanks to an anecdote told by Neil Gaiman, invokes the idea of a novel liberally illustrated is rather unfortunate as it sells the series short to potential readers. Not that it needs any further endorsement. But The Sandman is indisputably comics, and it is so much better off for that.

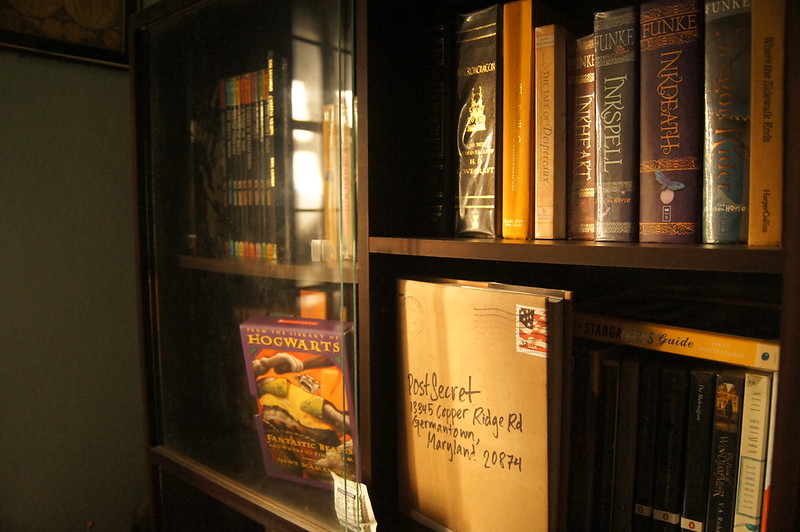

In the process of slowly saving up to buy a copy of the canonical ten volumes of Sandman I ended up deciding what my “Sandman Library” would have. Aside from the aforementioned canon, I wanted a copy of The Dream Hunters, arguably the title that set me on this path, as well as Endless Nights. I also wanted Alisa Kwitney’s The Sandman: King of Dreams “coffee-table” book, mostly because of how cool it looked. And, to cap off the collection, I wanted Hy Bender’s The Sandman Companion.

I never really expected to complete my Library, so much so that for a time, I referred to it as my ideal Sandman Library. The ten volumes alone that forms the bulk of it are expensive and hard to come by. The rest are even rarer and pretty niche, making chances of reprints slim. However, thanks to some fortunate turn of events, my ideal turned into reality at least in quantity, if not in composition, just in my second year of college.

I got everything I wanted, save for The Sandman Companion, but in its place I got The Sandman Papers, a collection of academic articles discussing the series. Overall, I could not call myself disappointed with what I ended up with. I have, after all, read everything Neil Gaiman wrote about the Sandman.

Coming from a childhood saturated with Japanese animation, it was quite a jump going into The Sandman. Gothic, at stretches bordering on eldritch, the art was, admittedly, not what I was expecting, especially considering that my earliest exposure to Sandman, no matter how trivial, is because of Yoshitaka Amano.

It is maybe largely due to this discrepancy in expectation and reality that I did not enjoy the first five issues as much as they are praised. They definitely have their moments but overall they felt like just a series of books. Well-written no doubt, but as far as an overarching plot is concerned, there was not much. The Sandman compilations I have, as pictured above, feature a blurb that claims you can read the series either in sequence or as standalone books. That claim holds strong for the first five compilations.

But Fables and Reflections is an inflection point. It may be ironic to say this of a volume that is explicitly a short-story collection but it is an excellent one to set the tone of the second half of the series. Destruction and Orpheus feature after being mere foreshadows of allusions in the first half. The history between the Endless siblings is also hinted at, laying ground for the developments that occur in the next volumes.

I call volume six an inflection point because this is the part where I will beg anyone who would care to listen: do not read anything from volume six onwards out of order. Damn whatever the blurb says.

It is also at this point where The Sandman had a curious effect on me. This is one of those anecdotes which might have a “mystical” air about it especially since we are talking about the King of Dreams here. But it happened, and you can make what you want of it. Back then, I would read a chapter (an issue) of Sandman just before I get whatever formal sleep I can. And that sleep would be refreshing. Sometimes, it would even end with the pleasant memory of a dream but overall, I just remember them to be good sleep, waking up feeling some kind of catharsis.

Lastly, I would say that Fables and Reflections marked the part where the series’ art style took a turn to my taste. I used to think that this is an effect of technology: that Sandman ran for so long that the evolution of comics printing is evident across its run. I used to think that it was largely thanks to technology that, by volume six, the art more closely–though ever so slightly–resembled the Japanese animation I am accustomed to. But lately I’ve come to learn just how much of it might actually be a creative decision on Gaiman’s part.

Or, maybe, it was still more of a creative constraint than decision. It’s just that Neil Gaiman knew his medium well and so played into its strengths and danced to its limits.

When I first took an interest in Sandman I remember foolishly wanting to collect the series on a per-issue basis. Call it naivete: the closest I even got to this was finding one issue–I no longer remember which–in a thrift sale in a shop in my local mall which sold an assortment of geeky items. Items I could not afford back then, relying on the mercy of my parent’s purse, but which I certainly returned to when, in adulthood, I found myself well-funded for my hobbies and sundry. Money does not change people, I guess.

Maybe today, if I ever come across another solo issue of the canon Sandman, I would buy it and then keep it in its case, never to be opened, preserved for posterity, and wait until the price for such things sky rockets so I could cash out.

Or maybe, nostalgia will get the better of me, and I will tear it open (after, of course, washing my hands very thoroughly) to breathe in comics fumes from the 90s, see the ads, and compare the original as published with its counterpart in the compilations.

My naive desire to own Sandman in its original serialization was somehow fulfilled a few years ago when Neil Gaiman decided to revisit this particular universe and wrote a prequel, Sandman Overture. Now, buying Overture on a per-issue basis (as opposed to waiting for the compilation that will surely come) was more than a matter of repressed-wish fulfillment. It was also a matter of logistics: my bookshelf, full as it is, could not accommodate another volume of Sandman. It could, however, fit individual issues in between the compiled volumes already housed.

Still, in some strange way, I got something I have already given up on.

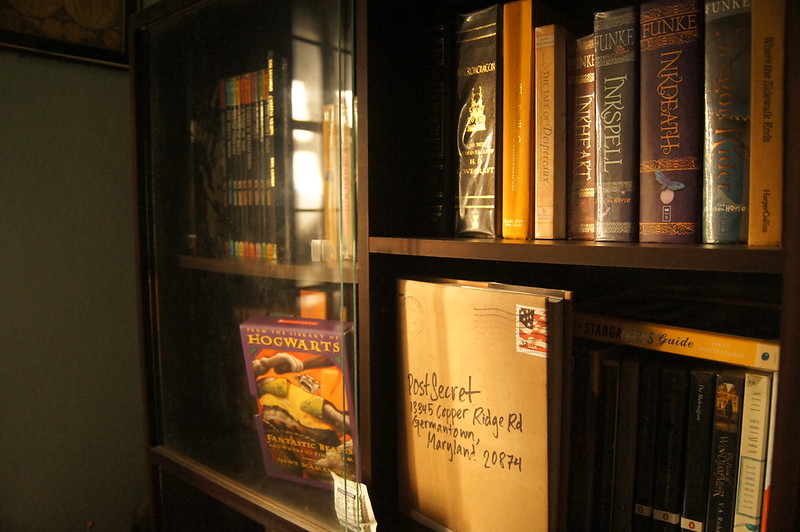

But it does not stop there. By the magical convenience of the internet and of public-key cryptography–the combination of which allows online shopping to be a thing–I have, recently, found myself in possession of the missing volume in my Sandman Library: Hy Bender’s The Sandman Companion.

My ideal Sandman Library has been realized in full. And more.

A person’s life consists of a collection of events, the last of which could also change the meaning of the whole, not because it counts more than the previous ones but because once they are included in a life, events are arranged in an order that is not chronological but, rather, corresponds to an inner architecture.

~ Italo Calvino in Mr. Palomar (?)

Ithaka gave you the marvelous journey.

Without her you wouldn’t have set out.

She has nothing left to give you now.

~ C.P. Cavafy, Ithaka

Like a stereotypical book maniac, I’ve always taken pride in owning “rare” books. Although over time I have come to realize I’m small fry, more like a kid calling trash and trinkets his treasure than a rich eccentric European Lucas Corso would have loved to plunder. My “rare” books are not exactly what book catalogs would list as rare or valuable; they are better termed as niche and maybe expensive, at least relative to my economic well-being at the time of acquisition. A first edition hard bound copy of Deathly Hallows, an omnibus of C. S. Lewis’ nonfiction, two volumes of Borges’ complete works, one for poetry and one for prose–you get the idea.

Getting a credit card gave my hubris something else to feed on. Books that are maybe not as expensive, though so niche as to be not distributed locally: Templar by Jordan Mechner, of Prince of Persia fame, a comics (“graphic novel”) about a heist perpetuated by members of the eponymous knight order; The Carpet Makers by Andreas Eschbach, a German sci-fi author who, as of this writing has not had much of his work translated into English; the complete Memoirs of Lady Trent by Marie Brennan, a beautiful (aesthetically and literarily) sci-fi series written as a pseudo-Victorian memoir. Maybe, just maybe, I could lay claim to having the only copy of these books for miles around, if not in the whole country.

That includes The Sandman Companion. Secondhand but in good condition and a first edition too. I would have loved to complete my Sandman Library sooner, maybe around the time I actually got the bulk of the canon, but I guess you can’t rush the universe’s schedule.

I no longer remember what I expected to get out of reading The Sandman Companion. But as I finally laid my hands on my own copy, the anticipation was stale, my expectations almost nonexistent. This was, to me, just a round of honor, just for the sake of completion. At this point I felt like I have read almost everything about The Sandman‘s canon: from interviews of Neil Gaiman, to his blog posts, to The Sandman Papers, and even King of Dreams. Maybe, it would be a shallow kind of debriefing, one where I’m told this is what this activity was going for (like it was not plain to see), this is what happened (like it did not happen to me), and thank you very much (I’d thank you too, out of courtesy).

I could not be more wrong. This Ithaka is not a resting place after all that I’ve encountered. It is more akin to a final adventure, the last one to give the whole escapade its form before I, maybe, really close off this library.

In format, The Sandman Companion is the odd one out in my collection. The bulk of the book is a transcript of Hy Bender’s interview with Neil Gaiman. The content is formatted in a way that is a bit reminiscent of magazines although maybe that should not be so surprising given the nature of the content. What is more unusual are the boxed insets of text that litter the interview transcripts: tidbits of information that is tangential to the topic at hand but was not directly brought up in the transcribed conversation. It reminds me of a common layout element in computer books for end users.

Reading the Companion is like re-experiencing the whole series in completely prosaic form. The discussion on each volume starts with a summary of the volume concerned but where this differs from my early Wikipedia-hopping is that Bender does not try to tell a story but, rather, explain the inner workings of Neil Gaiman’s creation. That the story is told in some way nevertheless is a mere side-effect of the process. Fittingly called, The Sandman Companion is like a pleasant tour guide in a beautiful country, pointing you to the wonders you shouldn’t miss without getting in the way of you establishing a personal connection with the place. Alas, the guide is only as good as the country.

Finishing the companion is like finishing the series a second time around. No less bittersweet, it is like a reunion with old friends concluded: we’ve caught up and reminisced, now it’s time to get up and go back into the world. But this time–and I would concede that this feeling might be unique to my circumstances as a reader and a Sandman fan–the conclusion comes with a sense of closure.

“[T]hat man would be scorned by all the others: by the king, by the conceited man, by the tippler, by the businessman. Nevertheless he is the only one of them all who does not seem to me ridiculous. Perhaps that is because he is thinking of something else besides himself.”

~ Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, The Little Prince

Reading the Sandman today is a completely different experience from reading it just as the series progressed. Today, it is unavoidable to be spoiled by statements about the series: how it is about change, that Morpheus dies in the end. Heck, it is not inconceivable that “spoilers” like these could be someone’s gateway into the series. It’s just that the Sandman canon will no longer be the terra incognita it was for those who were lucky to be able to follow along.

Although, as I could attest, spoilers are not necessarily a bad thing.

Perhaps ironically, what I envy those people is in how Sandman came in trickles for them. An issue a month, I feel, is just the right pace for the intricacy of Gaiman’s story to settle. Repeatedly reading Gaiman summarize his two-thousand-page opus as a story about change, and how the King of Dreams’ inability to deal with this causes his demise, made me take this message for granted that by the end of my first reading of Sandman I am unable to definitively illustrate how it is about change, and how this inability to accept change ultimately kills Morpheus. Shame for such a self-proclaimed Sandman fan.

What I realized from reading the Companion is that beneath the huge ensemble of artistic talent behind the series, beneath the prestige it has accumulated, the Sandman is actually more similar to St. Exupéry’s The Little Prince. It is about change, yes, but it is also about dreams and hearts–the things that make us human. Morpheus–like the grown-ups the titular prince encounters in St. Exupéry’s work–is too concerned with his function that he loses sight of how he and his function relates with everyone else. Despite being the anthropomorphic personification of dreams, there is nothing human in Morpheus’ core. And this inability to be human is what he cannot accept that he orchestrates his doom to give way to a new Dream. This time, a Dream that is human in form and humane in the execution of his duties.

I used to admire Morpheus’ approach in life for its stoicism. Perhaps I still do. In the celebrated special, The Song of Orpheus, Morpheus tells his son, the mythological poet who lends his name to the title, the lover of Eurydice:

You are mortal: it is the mortal way. You attend the funeral, you bid the dead farewell. You grieve. Then you continue with your life.

And at times the fact of her absence will hit you like a blow to the chest, and you will weep. But this will happen less and less as time goes on.

She is dead. You are alive.

So live.

Solid advice, even echoed by Morpheus’ down-to-earth (and, oddly, much more humane) sister, Death. When Orpheus visits her, she tells him

It was her time to go, Orpheus. People die. It’s okay. It happens.

Go on with your own life. You have many things to do: many songs to play and sing.

But what differentiates the results of Morpheus’ conversation with that of Death is their further reaction to Orpheus’ grief. Where Morpheus is dismissive and will not hear any more of Orpheus’ laments, Death is understanding and sympathetic to Orpheus’ plight. Ultimately, it may have served Orpheus better had Death not considered Orpheus’ plan to petition his case before the gods of the underworld. But what Death understood and Dream did not is that what mortals want above all is choice, a say in the matter. What Death’s boon gave Orpheus is some semblance of control over his plight. Losing Eurydice to a snake bite on their wedding night, Orpheus is a victim of fate. Looking back at Eurydice’s shadow just as he is about to step out of Hades’ is his own choice, his own failure. Hades’ may have been cruel, less than fair in the deal he struck with Orpheus. But alas, this misfortune is a direct result of Orpheus’ choices. His grief is, finally, his own.

I wanted to go a step further on this final storyline…and so started lobbying for DC to publish directly from Michael (Zulli)’s pencils.

Michael used to send me his pencilled pages, and they’d be breathtaking; and then they’d come back after being inked, and there would inevitably be some loss of detail… Inking came about because it’s easier to reproduce dark lines than feathery pencil work but by 1995, I felt that technology was at a point where anything could be scanned in, even pencils.

DC was very doubtful, so Michael drew a test page of Death with an eagle…the page that resulted was absolutely gorgeous, with no loss of detail… DC ultimately acceded to the idea and let Michael do issues 70 through 73 in pencils only, with no inker.

~ Neil Gaiman on the art style of the first half of The Wake as transcribed in an interview with Hy Bender in The Sandman Companion.

Among The Sandman‘s accolades is a World Fantasy Award for short fiction in 1991 courtesy of the issue A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Back then, this caused such a controversy that future editions of the World Fantasy Awards explicitly banned mere comics from being nominated. This had the curious effect that, to date, A Midsummer Night’s Dream bears the distinction of being the only comic to win the said award, let alone being nominated.

I have been told that a hallmark of good art is in how it changes with its audience. Something read in your teenage years could take on an entirely new meaning when re-read in your mid-20s. This is definitely true of The Sandman.

The debate about what is and what is not art will rage on, maybe until Death has put the chairs on the tables, turned the lights out, and locked the universe. But meanwhile, I imagine them–ideas, realized and repressed alike–going about their merry existence in some platonic realm, maybe Dream’s. Happy to be whatever they are, be that a comics series or a children’s book about wizards attending school. The vanity of labels does not concern them.

Life, after all, is but a dream.